Islamic finance is becoming an increasingly important part of the global banking and capital markets. In the Asia-Pacific region, Malaysia and Indonesia are among the largest markets for Islamic finance as a result of the predominantly Muslim population. In addition, regional financial centres such as Singapore and Hong Kong have adopted legislative and policy reforms to promote and facilitate Islamic finance transactions. This article provides a high-level overview of Islamic finance. It commences by defining Islamic finance. It then outlines the key principles of Islamic finance, examines its historical development and explains its key structures and processes. It concludes by outlining the issues and challenges and noting the development of Islamic finance in China.

What is Islamic finance?

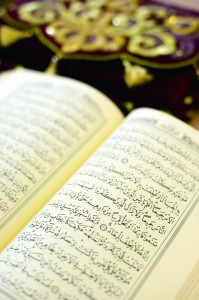

In basic terms, Islamic finance refers to financial transactions that are governed by Shariah law (i.e. Islamic principles). There are two important sources from which Shariah law is derived: the Quran, which is the scriptural foundation of Islam, and the Sunnah, which is the teachings and practices of the Islamic prophet, Muhammad. The process of interpreting these sources of Shariah law is called fiqh (which literally means “full understanding”) and it is from the interpretation of these two sources by Islamic scholars that Islamic jurisprudence arises.

What are the key principles of Islamic finance?

What are the key principles of Islamic finance?

There are some key principles on which Islamic finance is based. First, there is a prohibition on unjust gains made in the course of business transactions. Known as Riba, this prohibition rules out conventional loan structures for the reason that the payment and collection of interest in financing transactions is considered to be a form of usury and is prohibited. Shariah law also prohibits commercial transactions that are based on speculation (maisir), as this is akin to gambling, and also commercial transactions where the outcome is risky or uncertain (gharar). This creates difficulties for conventional insurance products and also conventional financing devices such as swaps and derivatives. In addition, investment in certain industries is prohibited (haram). These include gambling, pork production or consumption alcohol production or consumption. Thus, any financial transactions or financial products that are linked to these industries are likely to be prohibited.

How did Islamic finance develop historically?

To a large extent, Islamic finance grew out of Islamic revivalism in the 19th century. This revivalism was a reaction to corruption and lax moral standards that were considered to be prevalent in Muslim societies at the time. Two schools of thought emerged and mirror the divide in the Christian world between liberalism and fundamentalism: modernism and neo-revivalism. Modernism called for the reinterpretation of principles to accommodate social changes. Neo-Revivalism, on the other hand, did not support the reinterpretation of Islamic principles and advocated a literal approach to the interpretation and application of Islamic principles.

The divide between these two schools of thought was particularly evident in their treatment of the traditional prohibition on interest. According to the modernists, the focus of the prohibition was more on injustice and exploitation rather than on the use of interest per se. By contrast, the Neo-Revivalists argued that all interest was prohibited. In modern times, the views of the Neo-Revivalists have prevailed.

The development of Islamic finance has seen the emergence of Islamic banks and the establishment of Islamic banking entities by conventional banks. Although they form part of the broader banking group, these Islamic banking entities are kept structurally separate from the non-Islamic parts of the banking group to ensure that the principles of Islamic finance are not affected or undermined by the activities of the conventional banking business.

You must be a

subscribersubscribersubscribersubscriber

to read this content, please

subscribesubscribesubscribesubscribe

today.

For group subscribers, please click here to access.

Interested in group subscription? Please contact us.

你需要登录去解锁本文内容。欢迎注册账号。如果想阅读月刊所有文章,欢迎成为我们的订阅会员成为我们的订阅会员。

Andrew Godwin

A former partner of Linklaters Shanghai, Andrew Godwin teaches law at Melbourne Law School in Australia, where he is an associate director of its Asian Law Centre. Andrew’s new book is a compilation of China Business Law Journal’s popular Lexicon series, entitled China Lexicon: Defining and translating legal terms. The book is published by Vantage Asia and available at beta2.law.asia.