India Business Law Journal surveys the changes sweeping the Indian legal profession and identifies the best firms for key areas of work

By Alfred Romann

Now is a good time to be a corporate lawyer in India. Billing rates are going up. Salaries are going up. The amount of business is going up. There are more deals to work on, more billable hours to collect and more local and foreign companies doing more business than ever before.

“This year has been good. There is more growth than the industry can handle,” said Abhijit Joshi, of AZB & Partners. In an extensive survey of law firms and corporate counsel conducted by India Business Law Journal in June, his firm received one of the highest ratings. The top-rated firm in the country was Amarchand Mangaldas, closely followed by AZB & Partners and J Sagar Associates.

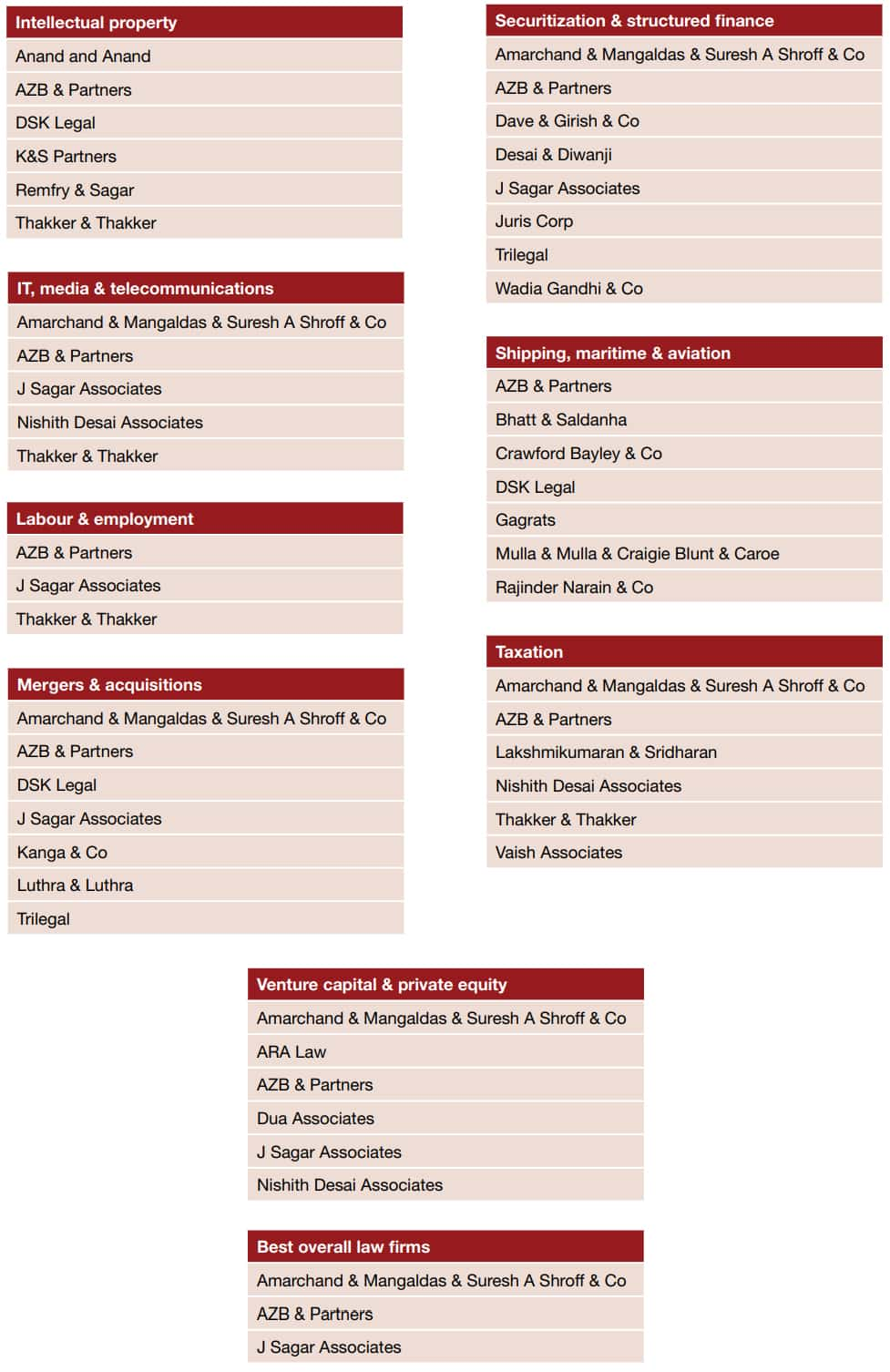

Other leading firms included Trilegal, DSK Legal, Luthra & Luthra, Nishith Desai Associates, Thakker & Thakker, Wadia Gandhi & Co, Crawford Bayley & Co and Dua Associates. (The full survey results are below.)

But for many of the country’s leading law firms, business success and the looming liberalization of the legal market have brought with them new challenges. Foremost amongst these is recruitment: while it is easy to find work from clients, recruiting experienced lawyers to do the work has become problematic.

There is a “shortage in the supply of quality commercial lawyers,” said Shardul Shroff, managing partner at Amarchand Mangaldas in Delhi. “Attrition is one of the biggest challenges.”

Then there is the speed of change. Laws that take a long time to draft have a very short shelf life.

“India is moving so fast that laws are obsolete almost as soon as they are passed,” said Joshi of AZB.

Then there is advertising, or the lack thereof. Indian law firms are not allowed to advertise, have a website or, theoretically, pass their business cards. This is a competitive problem and one that many of them would like to not have to deal with.

Another challenge that is often overlooked is the high cost of infrastructure, which in India can be as high as 50% of every billable hour. Office space in Mumbai and New Delhi can cost as much as in Tokyo or New York but lawyers cannot charge anything resembling the fees that lawyers charge in those two cities.

When foreign law firms set up shop in India, and sooner or later they will regardless of current laws that prevent them, these issues will have to be addressed. Indian law firms know this. They’ll have to be sharper, bigger and more visible.

Fragmented market

India’s fragmented legal market is ripe for consolidation but held back by the individualistic streak of many lawyers and the family-focused nature of the vast majority of law firms. But despite the fragmentation, the legal work being undertaken by India’s characteristically small law firms is becoming more complex than ever before.

“The complexity of deals is getting bigger,” said RJ Gagrat of Gagrats, a Mumbai firm with offices in New Delhi and Dubai that specializes in corporate work, aviation, finance, arbitration and dispute resolution, capital markets and projects. The firm has recently worked with Jet Airways on its acquisition of Sahara Airlines; the Public Group of Switzerland in acquiring a majority stake in Mediascope Publicitas, and Generacion Eolica International of Spain in setting up wind power companies in India.

“In the last few years, much has changed,” said Gagrat. “Indian lawyers are getting better every day at handling the bigger deals and more savvy in business.”

“In the late 80s we’d be terribly excited to do a joint venture agreement,” he said, whereas now joint venture agreements are considered everyday work. “Everyone is expecting a boom in the next three years.”

This boom is coming just as the demands for speed and quality of service are growing, said Dipak Rao, of Singhania & Partners, a New Delhi firm with 11 partners and 46 associates that has worked with Indian Railways, the Punjab State Electricity Board and on the acquisition of power companies in Latin America. “People want things to happen quickly. They want an answer before they send the e-mail,” said Rao.

Finding people

What is the biggest challenge facing law firms?

“People!” said Rohan Shah, partner at Mumbai firm Economic Laws Practice. “I don’t think we can invent enough lawyers to keep up with the growth.”

“People!” said Rohan Shah, partner at Mumbai firm Economic Laws Practice. “I don’t think we can invent enough lawyers to keep up with the growth.”

Best-known for its tax practice, his firm has worked on cross-border and infrastructure deals, including work with investors from the Middle East, South Korea and Canada.

“What we are seeing now is a gap in terms of the people we need and the quantity of work,” he said. “Your clients are growing so quickly that it is difficult to say you will not do more work.”

The problem is the “lower 10% of clients get left behind.” Recruiting people straight out of law school is possible but it takes time to train new lawyers and even these “freshers” are getting more expensive.

Not that long ago new lawyers were paid a pittance, if anything at all, to get experience in established law firms. Top graduates from the best law schools can now command monthly salaries of Rs40,000 (US$960) or more in exceptional cases. This is still much less than a young lawyer makes at a foreign law firm but the trend is upwards.

“When I started in this profession, people used to make a few hundred [rupees] and it took a long time to make thousands,” said Vikram Trivedi, managing partner at Manilal Kher Ambalal & Co, a full service firm that worked on the amalgamation of ICICI Web Trade and ICICI Brokerage Services and litigation linked to high-profile power projects.

The Indian education system has only recently started pumping out enough lawyers to keep pace with demand. In the last few years, a five-year undergraduate law programme that has expanded to universities across the country – separate from the traditional three-year post-graduate route – has gone a long way to filling the human resources gap.

“We now have the capacity to create 10,000 to 12,000 lawyers every year,” said Krrishan Singhania, managing partner of Singhania & Co in Mumbai.

ALMT Legal in Mumbai has also experienced “a big difficulty finding mid-range people”, said partner Vivek Daswaney.

This lack of people has led to chronic poaching and a constant shortage of lawyers with three to 10 years of experience. The result is that law firms are now finding they have to compete for the staff they already have.

“Until now we didn’t have attrition issues,” said Lira Goswami, a partner at Associated Law Advisers, a small but long-standing firm in New Delhi with two partners and 13 associates. “Usually they will go to a bigger firm or go abroad. A lot of people want to go abroad.”

It is easy to find people just out of school but “people who are right out of school are not that useful”, said partner OP Bhardwaj.

A foreign threat?

Few professions have been as instrumental as the legal profession in facilitating the march of globalization. And few professions have been as well placed to reap its financial rewards. It is therefore ironic that while benefiting handsomely from the globalization of other sectors, the Indian legal profession has fiercely opposed the liberalization of its own industry and the resulting entry of foreign law firms.

Despite this, very few lawyers and corporate counsel that responded to an India Business Law Journal survey voiced opposition to the entry of foreign firms into India. In fact, an overwhelming majority said they would welcome them.

In the words of one Delhi-based lawyer, “It is hypocritical to support the entry of foreign businesses, who we hope will become our clients, but not foreign law firms”.

Lalit Bhasin, founding partner at Bhasin & Co and president of the Society of Indian Law Firms, champions the opposite view. His long-established firm has four partners and 21 associates and works on aviation, labour law, dispute resolution, real estate and M&A.

The main problem facing Indian firms, he said, is losing staff to foreign law firms and corporations. Before foreign firms are allowed into the market, Bhasin believes that a code of conduct has to be established whereby foreign firms will refrain from poaching local lawyers. What’s more, he said, foreign firms have planned their entry into India very carefully. “It is a studied strategy. In the next 10 to 12 years the Indian legal market will open up,” he said. “[Foreign firms] will capture the market.”

The question is whether India’s law firms will be able to compete with their international rivals.

Size matters

One obvious challenge they face is their size. Limited by law to a maximum of 20 partners (although some of the larger firms have got around this restriction by structuring themselves as multiple-partnerships) and averaging around 30 lawyers in size, corporate law firms in India are smaller than their domestic counterparts in most other countries, let alone the big foreign firms that are waiting at India’s doorstep.

Thakker & Thakker, a Mumbai firm with offices in New Delhi and Bangalore, is one of many firms that is keeping an eye on the new Limited Liability Partnership Bill that could give legal partnerships the green light to expand beyond the 20-partner limit. Among its achievements, the firm has worked with Louis Vuitton Malletier on the first application for foreign direct investment in the retail sector.

Ghautam Bhat, an associate partner at Thakker & Thakker, said the Limited Liability Partnership Bill is likely to be passed in the near future and, most likely, with little debate. According to Shardul Thacker at Mulla & Mulla & Craigie Blunt & Caroe, a major Mumbai-based firm, many lawyers would like to keep the partnership limits in place as an argument for keeping foreign law firms at bay. The fact that Indian firms cannot expand beyond 20 partners makes direct competition with foreign firms unfair and lends a compelling argument to those seeking to keep foreign firms out of the country.

“You are putting shackles on your own hands,” he said.

Mulla & Mulla & Craigie Blunt & Caroe has 17 partners and more than 90 associates in offices in Mumbai, New Delhi and Bangalore. In the past year the firm has worked with Hindalco Industries on its US$6 billion acquisition of Novelis and for the Dharma Port Company on the US$442 million joint venture between Tata Steel and L&T Infrastructure Projects Ltd.

Mulla & Mulla & Craigie Blunt & Caroe has 17 partners and more than 90 associates in offices in Mumbai, New Delhi and Bangalore. In the past year the firm has worked with Hindalco Industries on its US$6 billion acquisition of Novelis and for the Dharma Port Company on the US$442 million joint venture between Tata Steel and L&T Infrastructure Projects Ltd.

Even if some firms have been able to get around the partnership limits, the caps may still impact expansion. “Today, is it limiting me? No. But going forward it could be limiting,” said Diljeet Titus of Titus & Co. His firm has 28 lawyers in its Delhi office as well as several associate firms.

Locally focused

While foreign firms are eager to work in India, the opposite may not be true. When law firms set up in offices in other countries, it is normally to follow their clients who have established businesses or investments in those countries. However, despite the recent wave of outbound M&A deals, few Indian firms plan to establish overseas offices to serve their Indian clients in foreign markets.

“Americans feel more comfortable going out,” said Gautam Khaitan of OP Khaitan & Co, a New Delhi firm with more than 30 lawyers. The firm has worked with Jindal Drilling on the acquisition of two rigs and on the acquisition of the UK’s Rosebys Fashions by GHCL.

“Mumbai people are very, very content. There’s a lot of work here. They don’t have to go looking for foreign work,” said Sunil Krishna of Krishna & Saurastri, a specialist intellectual property firm in Mumbai.

And the demand for lawyers in India is now high enough that corporations – let alone foreign law firms – are willing to pay top dollar to poach them. Krishna tells the story of one lawyer at his firm who was offered 20 times his salary to go and work for a corporation as in-house counsel. The lawyer later returned to Krishna & Saurastri as a partner.

Some firms say the 20-partner cap will keep them from competing with foreign firms but Anand Desai, managing partner of DSK Legal, dismissed those concerns as “rubbish”. Firms that want to expand beyond that limit have found ways of doing it.

Mumbai-based DSK Legal is one of the few firms that is considering the strategy of following its Indian clients into foreign markets. The firm has nine partners and 45 associates and focuses on private equity, M&A, distressed assets, real estate, energy, capital markets and intellectual property.

According to Desai, the increased foreign investment going into India is generating a lot of excitement, perhaps out of proportion with the actual dollar amounts.

“It is still the US and the UK but it’s coming from all over,” said Desai. “Everybody gets excited because it’s new. In India, five guys come and everybody gets excited. In China, maybe 200 guys come and nobody gets excited.”

No visibility

Aside from their small size, Indian law firms may face a competitive disadvantage due to their lack of visibility. Unlike their international counterparts, they are not officially allowed to advertise or have websites. This is a problem that many would like to address. Some are already pushing the boundaries of existing rules that prohibit “soliciting” by saying that advertising – when conducted through professional journals and resources – is not strictly soliciting.

Without a doubt, India is attracting a lot of attention but big deals with international players are a new phenomenon as is the amount of interest the country is generating globally. Much of this attention is still coming from the United States and the United Kingdom but, increasingly, investors from countries like South Korea are looking towards India, and Japanese investment is picking up again following the country’s economic recovery.

For these foreign investors, telling one Indian law firm apart from another is virtually impossible.

The challenges associated with lack of advertising have certainly been felt by one Delhi-based firm that has built a strong reputation on the back of specialization. Tuli & Co focuses almost exclusively on insurance work, an area seen as low rent until about 2000.

“We do pretty much only insurance,” said partner Neeraj Tuli. “We don’t do motor. We don’t do household. We do big, messy, complicated things.”

Insurance law is very niche and low key which would normally make advertising more essential than ever. In India, however, where law firms are not strictly allowed to take listings to inform prospective clients of their specializations and fields of practice, the restrictions on advertising can hurt. “It’s the ban on advertising that is a real problem,” said Tuli.

Difficult to define

Who are they? Where are they? What do they do? For the uninitiated this remains a mystery.

There are a lot of law firms in India that do a lot of good work but, hampered by their small size and inability to advertise, few of these firms have achieved the same level of international recognition as their counterparts in other emerging markets. This is a universal problem even affecting most large and medium-sized firms.

One such firm is KR Chawla & Co, a fast-growing Delhi practice with seven partners and 42 associates in offices in Bangalore, Chennai and Singapore. The firm has recently worked on high profile deals with Flex Industries, Era Construction (India) and Fantasy Hotels.

Another Delhi-based firm is PSA, a general practice firm headed by Priti Suri. With 12 lawyers, the firm is best known for its work in mergers and acquisitions, finance and regulatory issues. It is currently involved in several private equity transactions.

Kesar Dass B & Associates, another general practice firm, recently hit the headlines with its high profile appointment of RS Loona, former general counsel to the Securities and Exchange Board of India, to head up its Mumbai office.

Other prominent firms include Rajinder Narain & Co, which is best known for its experience in aviation law; Premnath Rai Associates, a Delhi-based firm that has been involved in a lot of biotechnology work; Lall & Sethi, which focuses on intellectual property, particularly in the media and film sectors; P&A Law Offices, a general practice firm that enjoys a close affiliation with international firm Jones Day; Suri & Co and Dave Girish & Co, both of which are best-known for banking and finance work; Lex Orbis, a prominent intellectual property boutique; and Corporate Law Group, a small firm that has been very active in international trade work.

India’s largest firm when measured by number of lawyers is FoxMandal Little. The firm has 36 equity partners, 13 salary partners and 220 associates in offices in 10 cities. In reality, the firm is not a single partnership but several partnerships brought together under a single brand name. By bringing together multiple partnerships the firm has managed to get around the cap on partner numbers and is building a countrywide legal brand.

The size of a single firm notwithstanding, it is not always easy to find the right firm to tackle specific problems.

“There are too many small sized law firms and there has to be a consolidation sooner or later,” said Sunil Seth, senior partner at Seth Dua & Associates. “The corporate culture has just arrived. It hasn’t sunk in yet.”

Khaitan & Co partner Upendra Joshi said his firm is a full-service firm “in the traditional sense”. The firm has 24 equity partners and 119 lawyers in offices in Mumbai, New Delhi, Bangalore and Kolkata. The firm deals with mergers and acquisitions, capital markets, private equity and other funds, infrastructure and real estate, banking, finance and project finance.

“It is difficult to maintain a critical mass in each critical area,” Joshi said. “Our approach has been to grow in each area.”

The firm advised Hutchison Telecommunications on the sale of its stake in Hutchison Essar, one of India’s largest M&A transactions. It also advised Suzlon Energy on its acquistion of a 75% stake in REPower Systems, a Hamburgbased wind turbine company.

Generalists

Few firms in India have specialized as much as Anand and Anand, an old firm that has built a very large practice around intellectual property (IP), although, as Binny Kalra explained, intellectual property itself is a broad area.

“The choice [to specialize] is almost inadvertent in a way because there is so much that goes into the field of intellectual property,” she explained. “Our hands are full with the work that we are doing.”

“There have been occasions when we sat down as partners and discussed whether we should stick with IP or expand into other areas?” said senior partner Archana Shanker. “We thought it would dilute us… There is so much to do in the field of IP.”

Anand and Anand has 12 partners and 67 associates in New Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai and Noida. The firm has worked with many prestigious international clients including Hilton International, Sony, Microsoft and Colgate-Palmolive.

Although many observers say specialization is the way of the future for Indian firms, Shanker says she sees the opposite happening.

“We don’t see people getting into specialization. There is a trend to expansion,” she said.

In India Business Law Journal’s survey of law firms and corporate counsel, Anand and Anand was widely seen as the top firm for intellectual property work. Other firms that featured prominently were Remfry & Sagar and AZB Partners.

Another firm that focuses exclusively on IP is Amarjit & Associates, launched by former Anand and Anand partner Amarjit Singh. The firm has five partners and 12 associates.

“Today, [clients] look for a person that is specialized in one field,” said Singh.

Outside the arena of intellectual property, most Indian firms still strive to be all-purpose entities despite their relatively small size compared to international firms. Some, however, have sought to focus their efforts.

One self-proclaimed boutique is ARA Law, a firm with two partners and 18 associates that focuses on corporate laws.

Another specialist is Juris Corp, a successful Mumbaibased firm that is better known abroad.

“Domestically we have a low profile compared to in Hong Kong and Singapore,” said partner H Jayesh. The firm focuses on financial deals and banking-related transactions but has found it difficult to define its niche in a market in which so few law firms are willing to lock themselves into a particular area.

Five years from now, said Jayesh, more firms will need to specialize to retain or increase their market shares but for now “we struggle to convince people that specialization is the way to go”.

The fear is that specializing will lead to a loss in revenues and less business but at least for Juris Corp the experience has been the opposite. And some other firms agree.

“Specialization is better than generalization,” said Seema Jhingan, a partner at LexCounsel.

The firm has six partners and 21 associates and sees itself as a full-service firm with particular expertise in IT and telecommunications, venture capital and private equity, M&A and infrastructure. In the last year it has worked on ownership negotiations concerning a foreign satellite and an outsourcing unit for a UK telecom services provider.

Despite recognizing the trend, lawyers at the firm agree that it will take time for specialization to work its way through the system.

“I think it is going in that direction… but it will take some time to get there,” said partner Dimpy Mohanty.

Another firm that has looked seriously at modernizing and incorporating multiple disciplines under a single roof is Dua Associates. Multi-disciplinary firms are not allowed in India but Dua has a separate consulting arm that keeps close ties with the law firm.

With 200 lawyers the firm is among the largest in India.

“You can only move towards specialization after you have a certain size,” explained managing partner CR Dua. “The only way specialization will work is if you have the work.”

Crawford Bayley & Co, a long-established Mumbai firm with 120 lawyers, has also noticed a trend among firms to zoom in on the areas they are best at.

“It is going towards specialization,” said partner Sanjay Asher.

Indian laws are changing so rapidly that it is very difficult to keep up with every change in every sector. That’s why many firms are specializing.

Some firms, like Nishith Desai Associates, are already providing specialized services. The firm has offices in Mumbai, Bangalore, Singapore and Silicon Valley. It prides itself on its research capabilities and has among its staff not only lawyers but also doctors, engineers and other technical people.

“Basically, we can talk the client’s language,” said the firm’s Vikram Shroff. “The main challenge that we face is in regards to systems and advertising.”

Being able to advertise would give the firm much wider brand recognition, Shroff said.

Some self-appointed full service firms like Suman Khaitan & Co have come to realize that specialization is the way of the future. The New Delhi-based firm has a single partner and 14 associates.

“Globalization is taking place. Countries like the US and Europe have advanced work. So the challenge is to deliver the same quality of work,” said associate Anoop Rawat.

Looking to the future

The business of law in India is changing daily. More than that, it is becoming more interlinked with the global business community. This demands more skill and knowledge.

A remarkably small number of firms are planning to go abroad to chase their clients as foreign firms have done, but a number of domestic sectors are looking prime for future expansion. Power, for example, “is going to be a very, very profitable sector,” said RJ Gagrat, of Gagrats.

The business of law in India is no longer what it used to be. A profession still dominated by family-owned law houses in which generations of lawyers honed their skills is now seeing the emergence of western style partnerships.

Home to 10 partners and 90 lawyers, Trilegal, is one such firm. It was set up by a group of young lawyers with “similar ideas of what a law firm should be”, said partner Akshay Jaitly. The firm has worked with Vodafone on its acquisition of Hutchison Essar, Citibank and the Mumbai Metro.

And growth prospects are good: “If we wanted we could go up to 110 or 115 [lawyers] by the end of the year”.

For them, as for many other lawyers in the country, the future looks good and the doors are wide open for lawyers who can make a bridge between India and the world.

“There is too much happening in India now. The unfortunate part is that [most lawyers] have no international experience… We do need expertise from abroad,” said Mona Bhide, a US-trained partner at Dave & Girish & Co. “It is a very interesting time to be a lawyer in India.”

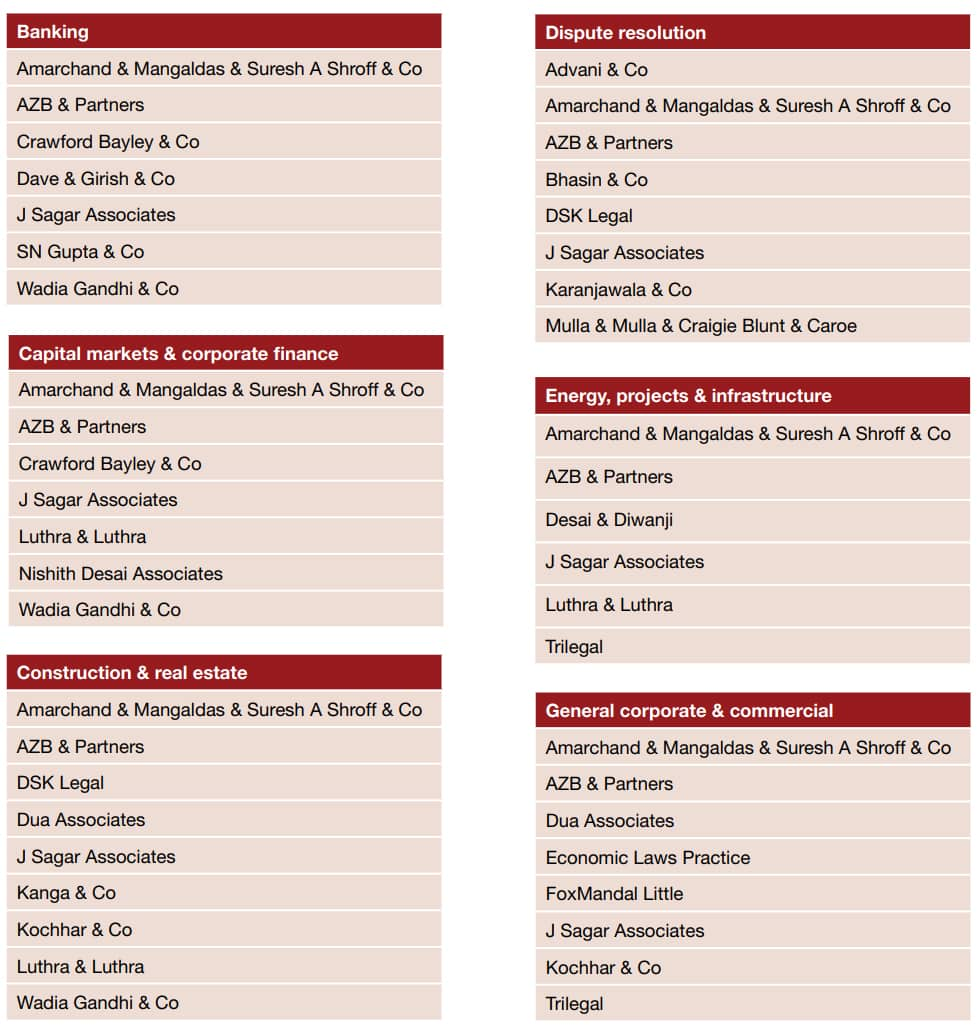

Leading the field

India Business Law Journal reveals the most highly acclaimed Indian law firms in key areas of practice. The results are based on a June 2007 survey of legal practitioners and corporate counsel

Firms in each table are listed alphabetically and not in rank order

The information in these tables is based on a survey conducted by India Business Law Journal in which more than 500 major law firms and corporate counsel were invited to participate. Law firms were requested to submit their views on the top firms, other than themselves, in a range of key practice areas and corporate counsel were also asked to name the best law firms in each practice area. The results of this survey are based exclusively on sourced factual material provided by legal practitioners and corporate counsel. They do not necessarily reflect the editorial opinion or position of India Business Law Journal.

The information in these tables is based on a survey conducted by India Business Law Journal in which more than 500 major law firms and corporate counsel were invited to participate. Law firms were requested to submit their views on the top firms, other than themselves, in a range of key practice areas and corporate counsel were also asked to name the best law firms in each practice area. The results of this survey are based exclusively on sourced factual material provided by legal practitioners and corporate counsel. They do not necessarily reflect the editorial opinion or position of India Business Law Journal.