Google was hit twice in October with hefty fines from the Indian antitrust watchdog for abusing its dominant position in the Android mobile operating system market and its Play Store policies.

The significant size of the penalties that aggregated to USD275 million, and the directives that accompany the two orders, strongly suggest that the Competition Commission of India (CCI) is not afraid to take action against unlawful conduct in the digital ecosystem, say legal experts who spoke to India Business Law Journal. The decision is also being monitored by regulators in many parts of the world.

“The two orders are a step in the right direction not only for app developers but also for Android users in India,” says Sonam Mathur, a New Delhi-based partner at Talwar Thakore & Associates who focuses on competition law.

On 20 October, Google was fined USD162 million for abusing its dominant position in the Android app store market to protect its market position and secure exclusivity at the expense of competitors. The CCI reprimanded the US tech giant for forcing smartphone manufacturers to pre-install its mobile suite or restrict users from uninstalling the apps.

Within a week, on 25 October, Google faced an additional fine of USD113 million for abusing its dominant position through its Play Store policies. It has been directed to enable external methods of payment.

The CCI’s directive has had a positive impact as Google has paused its global billing system in India, which was supposed to come into effect from 1 November.

The tech giant’s global payment policy came under fire in India, forcing Google to defer the deadline for Indian developers to integrate with Google Play Store’s billing system to 31 October 2022. It is currently evaluating its legal options as it prepares to challenge the CCI’s orders.

Google’s global billing system charges developers a 30% commission for transactions on its Play Store against 2% charged by other payment processing services. As Google Pay is pre-installed on Android smartphones, apps listed on its Play Store are forced to use Google’s billing service and pay a 30% commission.

Mathur appreciates that the CCI refused to interfere with the quantum of commission charged. A competition authority will typically refrain from setting prices. The CCI has instead prescribed forward-looking factors to guide Google’s future conduct, policies and prices, she points out.

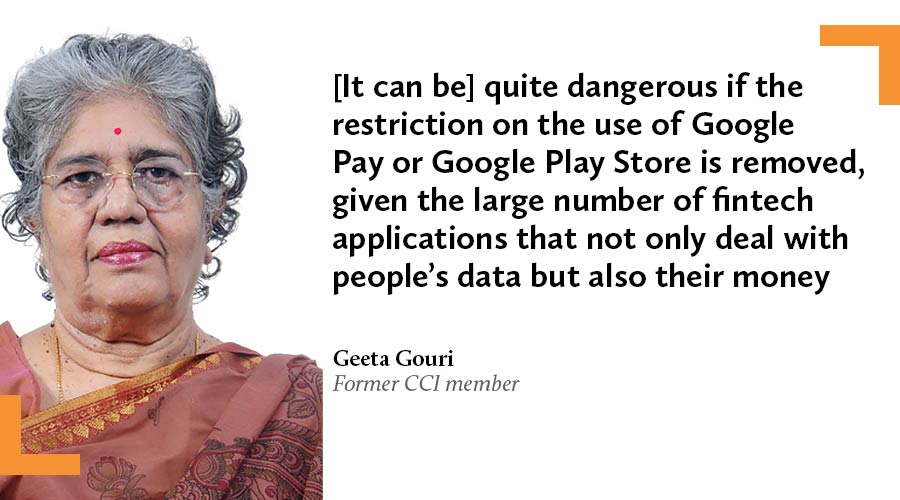

While it is true that the Google search engine is dominant, former CCI member Geeta Gouri questions whether it is right to say that the US tech giant has used its dominance to insist on the use of its global billing system, and leverage it to increase its market share.

While the CCI seems to have set the stage for other antitrust authorities investigating Google for similar conduct, some legal experts have raised concerns over security risks that could arise should Android users decide to use third-party payment channels.

The Google decision was rushed through just before its former chairman, Ashok Kumar Gupta, retired on 25 October, and ignored the security aspect, a few experts pointed out.

It can be “quite dangerous if the restriction on the use of Google Pay or Google Play Store is removed, given the large number of fintech applications that not only deal with people’s data but also their money,” says Gouri.

“I am not justifying what Google has done but I am trying to see what would happen using third-party payment apps,” she says, adding that not enough research has been undertaken on the security aspect of using third-party payment apps.

Google told the media that India’s antitrust decisions were a major setback for businesses and consumers and, more importantly, they could expose users to “serious security risks” and increase costs for Android users.

“Safety measures will need to be put in place given that the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) app is still very new,” warns Gouri. The UPI, an instant real-time payment system developed by the National Payments Corporation of India, is used on mobile devices to facilitate the instant transfer of funds between two bank accounts.

The CCI’s directives, although great for the app developers’ community, are a bit ambiguous, says a Mumbai-based antitrust lawyer. “How they will be interpreted is going to be challenging for the CCI,” he says.

The CCI directive states that Google cannot impose any unfair, unjust or discriminatory conditions. “All Google has to do is justify why it is fair,” the lawyer points out.

The CCI has given Google ample leeway to amend its behaviour, stating that the US tech giant should provide app developers access to data generated through the app subject with adequate safeguards. The question being asked is who should identify what is adequate.

If Google is to define adequate safeguards, the CCI directives will not be so problematic for the tech giant, the lawyer points out.

The CCI’s order is more ex-ante than ex-post and based on allegations from a few sellers rather than consumers, Gouri points out. Ex-ante rules can be subjective. “There is no assessment of fairness and how competitive constraints operate,” she says.

The Mumbai-based lawyer agrees and adds that when there is no legal or policy framework governing the operations of digital platforms, it is questionable on what grounds the damages are calculated.

India’s decision could have international ramifications as antitrust authorities across the globe are looking into the in-app payment policies of Google and Apple. Australia and Germany have reportedly taken interest in the CCI’s decision. The European Commission, Korea Fair Trade Commission and antitrust authorities in the US are also among those evaluating the situation.

The Briefing is written by Freny Patel