As the scope of services that lawyers provide has broadened in the past few decades, so too has the basis on which lawyers charge fees for their services. No longer do lawyers charge purely on the basis of time, although in most jurisdictions this is still one of the main measures by which lawyers value their services. Instead, many different fee options are used, including fixed fees and fees that are determined by reference to the value of the services that the lawyer has provided and now also contingency fees.

Increasingly, jurisdictions around the world are permitting lawyers to adopt a broad range of fee structures in both contentious (e.g. litigation) and non-contentious matters. Litigation is more sensitive, and therefore subject to more restrictions than non-contentious matters. The reason for this is that the costs of litigation are high, often beyond the payment ability of the parties. This gives rise to concerns about access to justice and highlights the need for a system of legal aid. In addition, in jurisdictions where the losing party is responsible for paying the costs of the winning party, the costs of litigation are often unpredictable and can be punishingly high. This has led to the emergence of legal expenses insurance to cover the expenses of litigation.

One of the most sensitive issues has been whether lawyers should be able to charge contingency fees in litigation proceedings. This column looks at the rules governing contingency fees in certain common law jurisdictions, and in mainland China. It starts by defining “contingency fees” and then looks comparatively at the position in the relevant jurisdictions. Finally, it examines briefly some of the arguments for and against contingency fees.

What are contingency fees?

This term is used in a broad and also a narrow sense. In its broad sense, it refers to any arrangement under which the fees that a lawyer charges depend on the outcome of the case. In this sense, the term includes “conditional fee arrangements”, under which the lawyer agrees that he or she will only collect a fee if the client wins (i.e. “no win, no fee”). Sometimes this involves the payment of a success fee on top of the usual fees that the lawyer would normally charge in the event that the client wins.

In its narrow – and most controversial – sense, the term refers to an arrangement under which the lawyer agrees that if the client is successful and obtains damages or compensation from the other party, the lawyer’s fees will be based on a percentage of the damages or compensation that the client receives (also known as “damages-based contingency fees”). In other words, the lawyer’s fees will be paid out of the damages or compensation that the client receives.

For many years, most jurisdictions in the US have permitted lawyers to charge contingency fees according to both definitions, except in criminal cases or certain types of family law claims. In particular, contingency fees are very common in personal injury cases. Although the rules in the US are relatively liberal as compared with other jurisdictions, there are still restrictions. For example, most jurisdictions require contingent fees to be “reasonable” and the fees are usually set at 33-45% of the recovery amount.

You must be a

subscribersubscribersubscribersubscriber

to read this content, please

subscribesubscribesubscribesubscribe

today.

For group subscribers, please click here to access.

Interested in group subscription? Please contact us.

你需要登录去解锁本文内容。欢迎注册账号。如果想阅读月刊所有文章,欢迎成为我们的订阅会员成为我们的订阅会员。

Andrew Godwin

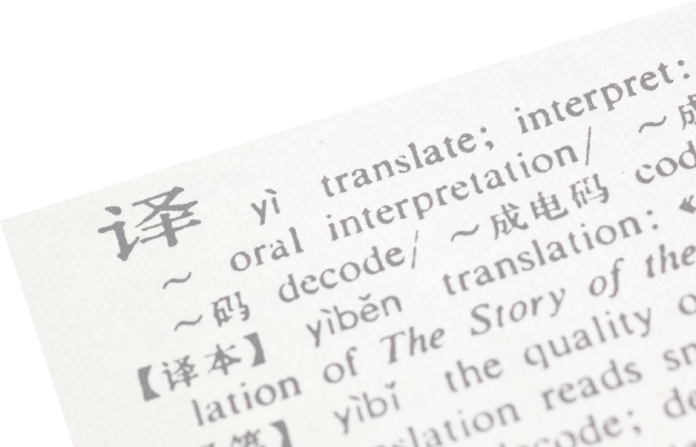

A former partner of Linklaters Shanghai, Andrew Godwin teaches law at Melbourne Law School in Australia, where he is an associate director of its Asian Law Centre. Andrew’s new book is a compilation of China Business Law Journal’s popular Lexicon series, entitled China Lexicon: Defining and translating legal terms. The book is published by Vantage Asia and available at beta2.law.asia.